The 40th anniversary of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind offers an opportunity to look back at one of the most fascinating films of Steven Spielberg’s career. Blending conspiracy thriller, familial drama and wide-eyed science fiction fantasy, Close Encounters is an expansive and yet deeply personal film for Spielberg that remains so deeply woven into our cultural fabric that we can barely look out into a night sky without humming the iconic five tones theme. It’s a masterpiece, but one its director has expressed concern about.

Looking back at the film for its twentieth anniversary in 1997, Spielberg said that Close Encounters is very much a product of his youth and one that he could never make in the same way today. “I see a lot of naivety,” he said. “I see a very sweet, idealistic odyssey about a man who gives up everything in pursuit of his dreams, or his obsession… In 1997, I would never have made Close Encounters in the way I made it in 1977 because I have a family that I would never leave. I would never drive my family out of house and home and build a papier mache mountain in the den and then further leave them to get on a spaceship and perhaps never return to them. That was just the privileges of youth.”

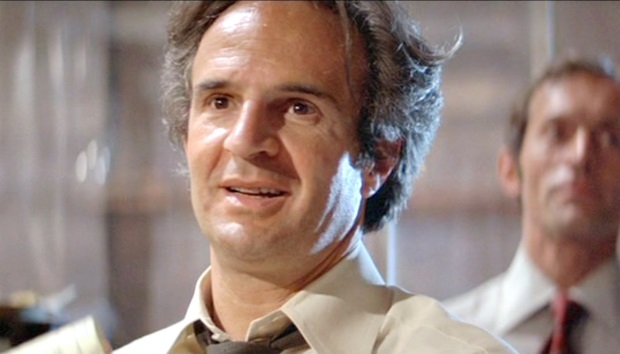

Childhood and naivety again played a part in his comments ten years later, when he spoke for the film’s 30th anniversary. Referring to the casting of Francois Truffaut, whose connection with a childhood sense of wonder made him the perfect choice for the idealistic Lacombe, Spielberg said: “We made this picture in the spirit of childhood and believing in things that don’t make sense, that only children believe in because it doesn’t have to make sense for a child to believe in.”

Spielberg’s right (it is, after all, his film), but just because Close Encounters has a childish innocence to it, doesn’t mean it’s immature or that it has nothing to teach us in the modern day. In a film culture where blockbusters have a distinctly adult feel or are shot through with a humour that undercuts their sincerity, the earnestness of Close Encounters is perhaps more important than ever. Here’s a film that believes everything it’s saying, that really subscribes to the idea that you can wish upon a star and have your dreams come true. Few films today have such faith.

More importantly, Close Encounters offers a balm for a divided world. Hatred is on the rise again and our leaders are doing little to calm the fires. Whether it’s Schindler’s List and Amistad or E.T. and The Terminal, Spielberg’s focused on prejudice and the connection needed to counter it throughout his career. It’s a deeply felt desire for harmony that links back to his childhood. Having suffered anti-Semitic abuse and other forms of bullying while growing up, Spielberg celebrates outsiders in his movies, showing how they enrich our lives (as in The Terminal) or demanding that they’re protected by those more privileged (Schindler’s List).

Close Encounters is no different. Roy, Barry Guiler and Jillian Guiler become outsiders after their visitations. When an anguished Roy storms out into his back garden, cursing the heavens and demanding to know what the shape he sees in his mind means, he’s speaking for anyone who’s ever felt different. Later, when his family has left and he’s in his den working on the gigantic Devil’s Tower model, he peers through his curtains at the happy suburban families going about their day outside and miserably returns to his project. It’s a moment loaded with meaning. Both admiring of and frustrated by suburbia, Spielberg strikes a bittersweet tone by portraying the tragedy of the person who feels like he can’t belong in place where everybody else can.

In many ways, we’re less able to belong now. Years of fearmongering has convinced so many of us that the people who are different to us are out to harm us. We’re a fractured planet, and if Roy were to peer through his curtains in 2017, it’d probably be out of a fearful, Fox News-driven desire to work out which of his neighbours he should fear the most. It’s difficult to understand how our deep divisions can be healed – and terrifying because of that lack of insight.

Close Encounters doesn’t offer an answer (few films can), but it does have the right kind of sentiment. In the 2007 interview, Spielberg also spoke about the iconic moment when Barry Guiler opens the door to the visitors and is bathed in an orange/yellow light that’s both wondrous and terrifying. It’s an image he’s spoken of before, describing it as his ‘master image’: a single shot that can be used to sum up his entire career and the themes he’s explored throughout it. In 2007, he expanded, saying:

“When I designed that shot, and when I wrote the script, that was very symbolic of what only a child can do: trust the light, open a door when an adult would run and hide and say, ‘Don’t open the door. Lock the door. There’s things outside that you don’t understand. Things that could kill us or change us…’ For me, thematically, Close Encounters is all about children opening doors onto beautiful sources of light. In 2007, the 21st Century, sadly people have a different interpretation of opening doors.”

This is Close Encounters‘ greatest lesson. Yes, the world is scary and yes there are terrible things out there, but there are also incredible, wonderful, life-changing and life-affirming things too. We’re all outsiders in some way and we should all do what we can to ignore the fears and frustrations that are poured into us and trust a little more. Forty years on, we remember those five tones, but what makes Close Encounters truly endure, what makes it the masterpiece it is, is that it asks us to believe not in aliens, but each other.