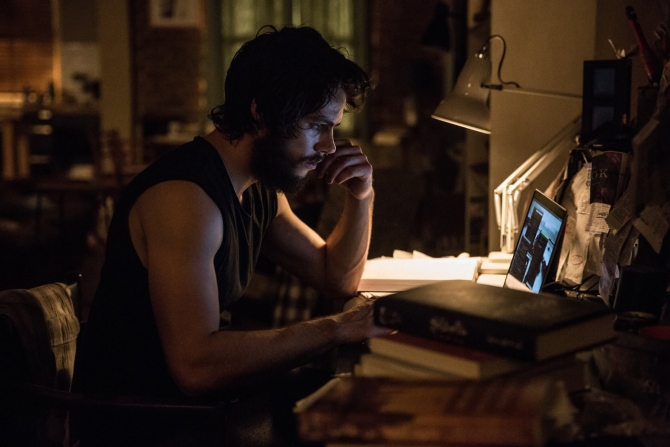

It comes to something when you’re so lily-livered that gunshot makes you jump even after you’re told that it’s coming. It’s early October 2016, and I’m sitting in a darkened warehouse in London where filming on American Assassin is taking place. Actor Dylan O’Brien is on set, holding a machine gun in a darkened tunnel. Illuminated by diffuse light from above, he looks lean and bestubbled, his firearm pointed straight towards the camera.

A crewmember has dutifully handed out ear plugs with the warning that the gunfire is going to be pretty loud. The ring of a bell and a shout of “Rolling!” means filming has commenced and, right on cue, O’Brien squeezes the trigger. A thunderous volley of bangs rings out, making your humble writer lurch forward in his seat; we hear the shots before we see the muzzle flash illuminate the scene on the monitor, white and jagged like a bolt of lightning.

Before we know it, the scene’s over: this is but one shot in a tense sequence which takes place in a tunnel somewhere under Rome; actually a long wooden construction erected in the Gillette building in west London. Shooting on American Assassin has been under way since September, and as we arrive on the darkened set, there’s a jovial atmosphere in the air that seems to emanate from producers Lorenzo di Bonaventura and O’Brien and passing on through the cast and crew. From the early footage we’ve seen, it’s clear that American Assassin is a brooding, violent film, but the laughter and joking on set has the convivial tone of a cafeteria: albeit one full of props, set-pieces and a generous fug of stage smoke.

Directed by Michael Cuesta (best known, perhaps, for his work on TV’s Homeland, Six Feet Under and Dexter), American Assassin is the first movie adaptation of a series of thrillers written by the late author Vince Flynn. It introduces tough CIA operative Mitch Rapp, a terrorist hunter distinguished by his tendency to cross moral and legal boundaries during his line of duty. Flynn wrote a total of 13 Rapp novels before his passing in 2013, aged 47; American Assassin was the 11th in the series, yet its events take place before the preceding Mitch adventures. This gave producers Lorenzo di Bonaventura and Nick Wechsler a useful means of introducing Mitch, and at the same time distinguishing the character from the likes of Jack Bauer, Jack Reacher or Taken’s Bryan Mills; as played by O’Brien (The Maze Runner, the Teen Wolf TV series) Mitch is a fresh-faced recruit in his mid-20s rather than the seasoned 40-something we’re used to seeing in action thrillers or spy novels – and, for that matter, in Flynn’s other books.

“That’s something I think about a lot with how I want to play this guy,” Mitch says between takes. “Something that’s really great about the character is the emotional aspect – for him, what he goes through, he always holds that with him. You’re literally watching a guy deal with an aftermath of this dramatic phase of his life. It completely changes him. It’s fascinating to watch someone toe the line of having to yes, be as Hurley always tries to teach Mitch to take the person out of it, take the emotion out of it, this is a job. This is what we do. Going after terrorists is only going to lead down a bad path, and it’s never going to kill you the way you think it will. It’s like a struggle that I find fascinating – this kid, the reason he’s pursued this is because of vengeance, in a sense. He wants to right something that happened to him.”

Rapp, then, isn’t quite a finished product: he can handle himself in a fight and fire a gun, but he isn’t yet the state killing machine the CIA wants to create. Michael Keaton’s Hurley, on the other hand, already is: an operative since the Cold War, he has a few miles on the clock but isn’t even considering taking retirement. Instead, he serves as Rapp’s handler and trainer, taking Mitch through his paces and drilling him in the subtleties of hand-to-hand combat. This is demonstrated in a woodland scene we’re shown in early form: Dylan O’Brien’s rookie going toe-to-toe with the formidable action star Scott Adkins. It’s to O’Brien’s credit that, despite being far more slight of frame than Adkins, he still convinces as a fighter skilled and pugnacious enough to best his opponent in a fight. (Keaton, unnervingly, circles round the pair, occasionally throwing an unhelpful blow or word of discouragement.)

If all this makes the Mitch-Hurley relationship sound like a mentor-mentee dynamic (like Rambo and Colonel Trautman, say), rest assured that American Assassin’s screenwriters (credited to Stephen Schiff, Michael Finch, Edward Zwick and Marshall Heskovitz) have done their utmost to upend that familiar narrative staple: there’s a spiky antipathy between the two, with neither, it seems, particularly approving of the other’s philosophy towards their jobs.

American Assassin therefore provides an origin story of sorts for its CIA hero, showing his training, his first use of lethal force, and his first taste of action in the field: all we know right now is it has something to do with terrorism and nuclear weaponry, which is a reliable recipe for disaster in an action thriller.

O’Brien is an interesting choice for the lead, particularly given that earlier versions of this movie had the somewhat older (and burlier) Chris Hemsworth attached. Yet it’s easy to see why O’Brien was cast once you see him in context; he can do the action stuff, sure, but there’s also a vulnerability and likeableness to him. de Bonaventura agrees that a watchable action lead needs something other than stoicism; an Achilles heel, a sense that they’re human just like the rest of us, even if they can kill bad guys in a knife fight.

In person, O’Brien comes across as refreshingly down-to-earth and thoughtful. He eats spaghetti Bolognese from a polystyrene container as we talk about his character and the specifics of firing guns in movies. A noteworthy background detail: it’s the 7th November, there’s a cold snap in the air and there’s just one day left before the polls open in the US. The word is that Clinton’s well ahead, but there’s still that lingering fear that Trump might actually win.

“Turn that thing off,” O’Brien says, motioning to my voice recorder with a plastic fork, “And I’ll tell you exactly what I think of Trump.”

Di Bonaventura is less circumspect, and argues that Trump’s politics are appealing to people who are looking for a simple message in an increasingly confusing and scary world. He argues it’s why escapist, superhero entertainment has proliferated since 9-11; we’re subconsciously looking for an alternate world where there are absolutes of good and evil and heroes to save us.

“It’s a simplistic solution, but it’s also partly wish-fulfilment,” di Bonaventura says. “Don’t we wish [terrorism] would just go away? Yeah, I do. It was weird, when we were picking locations, that we think about security. That’s weird, you know? Not many years ago, we shot in Egypt, and we hardly thought about it. Or Jordan. I mean, we thought about it, but today you wouldn’t even consider it. The prism of our decision-making has completely changed – we hired security firms to do an analysis of London. What’s the risk of filming in London? Which is crazy. That’s a different world.”

American Assassin, the producer adds, is set in a world of moral ambiguity and, to use a modern phrase, an era of asymmetrical war where the enemy doesn’t wear a uniform. It’s an action film, sure, but there’s more than a hint of real-world uncertainty: de Ventura suggests that the movie doesn’t do what Rambo did and paint one specific country as an inhuman aggressor.

Given that Di Bonaventura is most famous, of late, for producing the Transformers movies, American Assassin sounds on paper like a much smaller production. In reality, this is only like saying that Alien was a smaller production for 20th Century Fox than Cleopatra; di Bonaventura says there are about 300 people on the payroll, versus about 4,000 for one of the Transformers movies. There are motor homes and tents all over the grounds of the Gillette building, an art deco industrial complex which, once we’re through the very tight security, looks for all the world like the byways and alleys of Elstree Studios. The publicist tells me another film was shot here in 2009, so it looks as though it’s becoming something of a destination for film productions.

Later, I’m taken to an edit bay where the footage captured so far is being carefully assembled. What I’m shown is evidently a work in progress, but the action’s clearly going to be bloody and hard-hitting; there’s a quite impressive overhead shot of Mitch bloodily shooting a bunch of guys in the head. Another sequence where Rapp gets in a fight with Shiva Negar’s agent, Anika, in a bathroom; it’s fair to say she gives as good as she gets, but it remains a harsh scene. I’m also shown some sort of VR training sequence, in which Mitch and a bunch of other guys are holding guns and shooting digital terrorists or something like that. The hardware they’re using simulates the pain of a gunshot somehow. I’m told that Mitch fights through the pain and, frothing at the mouth, manages to let off a shot: a sign of the character’s fighting spirit.

I sort of feel as though the producers are using me as a Guinea pig here; I’m shown two sizzle reels which contain some common footage, but the latter is more verbose and revealing of the themes and plot. They ask me which I prefer; I venture to suggest that the first one, which is more visual and less dialogue-heavy, is the more cinematic. They nod at this, seemingly satisfied, or maybe just being polite. I get a similar sensation from the bathroom scene; is it too much? Will they lose the audience with this?

I’d also argue that, from the little I’ve seen, Negar, who plays a mysterious Turkish agent named Annika, might wind up being the break-out of this movie. She seems like a really good actress, and there’s something quite moving about the fact that she’s drawing on personal experience in playing this character. Born in Iran, her family moved to Turkey, where, she says almost off-handedly, they wound up in prison. After that, they migrated to the US; Shiva is therefore trilingual, just like her character in the movie.

“We ran away, we got caught in Turkey, we were in jail for a couple of months… so I can really relate to her,” Negar says of her character, between dabs of the makeup artist’s brush. ” She has that vulnerability but you don’t see it 95 percent of the time. You can see there’s a lot of rage in her, but she keeps it professional at all times. That’s interesting to play. There are certain small moments she has with Mitch. I guess when you go through that painful experience of losing your family, that you don’t give into the pain. It toughens you up, which is why she comes across as very strong. It’s second nature to her.”

I’d love to ask her more about her background and experiences, but she’s whisked off to rehearse a scene: more smoke, more darkness, more flashes of gunfire. Oddly, among the brief, frenetic half hour or so while I’m on set, Taylor Kitsch is here, sitting in a canvas chair with a few other actors who I don’t recognise. It seems slightly odd that I’m not introduced to Kitsch, given that he was the lead in two pretty big films: John Carter and Battleship. Then again, there may be a good reason why Kitsch is being kept at arm’s length; he’s another agent, codenamed Ghost, and from his cold demeanour and military outfit, I get the impression he winds up being one of the film’s villains.

American Assassin has also been filming in Birmingham and Glasgow, and there’ll shortly be two more weeks to shoot in Rome, mostly on location, the publicist says. On my way out, I see a bunch of guys packing up trucks full of cables and scaffolding; the circus is rolling on to Rome.

It’ll be interesting to see what the politics of this movie are like. The writer of the books was a story consultant on 24 for a time, and Jack Bauer was one of those characters for whom cruelty and a disregard for human rights were seen as a virtue. The message of 24 seemed to be that the ends always justify the means; there really are occasions when torture and murder are the just things to do. I wonder whether American Assassin will deal with this kind of certitude, where the extremes Mitch goes to are always justified because he’s trying to save the world.

While the politics of American Assassin aren’t clear to me, de Bonaventura nods enthusiastically when I bring up films like The Ipcress File or The Spy Who Came In From The Cold: they’re stories that show that there’s a psychological consequence to violence, even for the perpetrators: they’re lonely, bruised, pushed to the fringes. If American Assassin can introduce a hint of that, and make Mitch something more than a killing machine like Jack Reacher or Bryan Mills, then that would really mark the film out as a fresh breed of action hero for the 21st century.