This review contains spoilers.

1.1 The Pilot

The New York City of 1971, the New York City of The Deuce, is before my time. The days of fabled sleaze and seduction, vibrancy and violence, which piled onto the sidewalks like so many ripped garbage bags, have long passed… albeit, the garbage stacks remain. Even upon first visiting the Big Apple nearly 20 years ago, Giuliani Time was deep in the rearview, for better or worse. The crime rate is still way down, and you could walk through Times Square without being bombarded by trash, porno theaters, and rented flesh; but you also couldn’t go there without tripping over short-tempered Mickey Mouse and Spider-Man mascots trying to pimp their own wares at five bucks a photograph. Nor can you find a city as dangerously kinetic as the rose tinted postcard HBO’s The Deuce is using to cut lines of coke-shaped nostalgia on.

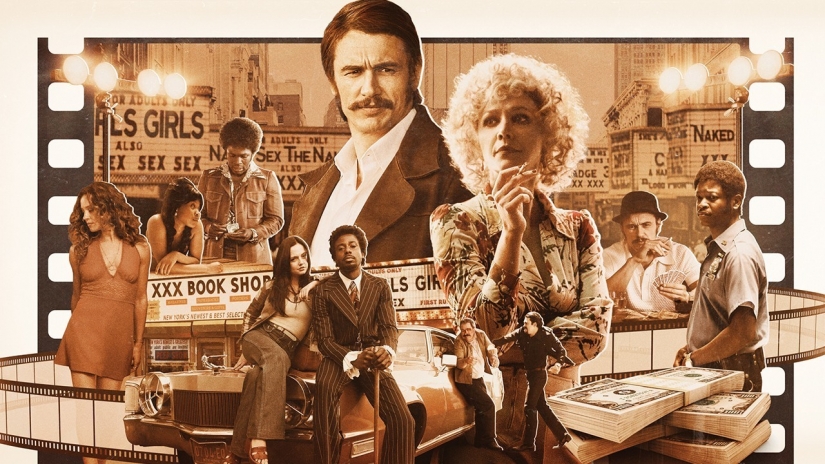

As HBO’s big freshman effort for the fall of 2017, The Deuce is stomping on familiar ground after the premium network’s infamous 2016 disaster, Vinyl. That supposed sure bet, with the pedigree of Martin Scorsese and Terrence Winter, was a similar time warp to purported glory days of gritty urban decay. And it misfired with spectacular awfulness. Luckily though, David Simon’s The Deuce appears to earn its swagger and big dick swinging bravado while longingly staring at days, and gin-soaked nights, gone by. It’s of course impossible to judge a whole season off of its first episode, particularly a pilot at that, but The Deuce like HBO’s last fall gamble, Westworld, leaves the gate strong by providing a sinister and slyly intoxicating storytelling web to get wrapped up in.

This first episode of a television series that will purportedly explain why the hell people thought porn would go mainstream in the 1970s (and how it kind of ultimately did, even if it failed to become the date night fantasy that Travis Bickle dreamed it to be) is off to a strong start simply by grooving off the high that cesspool-snorting can create. It is not yet clear whether eight episodes (or years) of foreplay in building the modern porn industry will make for exciting television, but it certainly makes for a wistful pilot crackling with intensity in a period set before crack was even a thing.

Opening in 1971, The Deuce’s title refers to two things: the nickname 42nd Street earned back in its grimiest heyday (particularly as it cut between Hell’s Kitchen on 9th Ave. and past Times Square and into Bryant Park on 6th Ave.), as well as the fact that its lead actor James Franco plays two characters: Vincent and Frankie Martino.

We’re introduced to the first bloke early enough since the 90-minute premiere begins with Vincent taking a late night beating and a whole hell of a lot of abuse because he looks like his twin brother, Frankie. Vinny is a part-time bartender hoping he’s on the rise while Frankie is, by all-accounts, a full-time scumbag. Over the course of the pilot, Vincent is trying to make something of himself even though he works a dead end job deep in Brooklyn while also attempting to move his way up as a manager at a questionable Korean restaurant in the heart of Times Square. When we meet him, he’s also at the tail end of an all-around lousy marriage which concludes with him walking out on two children, even if his wife is an AWOL space case.

It is hard to know whether audiences are supposed to relate to Vincent or judge him too harshly—after all, he is flirting up a 20-year-old college student before the end of the hour while Gary Puckett croons “Young Girl” in the background—but Franco portrays him with plenty of affability. Electing to underplay his working stiff who hopes to make more out of his time on 42nd Street than pouring drinks for shady cops and a legion of lushes, he comes off as a pretty level-headed dude (at least at first), even as he moves into a nearby midtown hotel so dubious that he is probably the only local professional renting rooms for longer than an hour.

This is likely buttressed by the fact that Franco is also playing Frankie with all the hammy nastiness of a Harry Osborn who actually grew up in Queens. Frankie is the kind of guy who lets his brother take the heat from Mafioso goombahs while he lies low and pretends he’s in Vietnam serving his country as a sergeant while, in actuality, he’s collecting money on the side from Vinny. The single scene of the night between the brothers Martino is amusing, if for no other reason than to see the two sides of Franco brought to the fore: the dedicated leading man with a penchant for the unconventional and the larger-than-life character actor with matinee idol good looks. I’m not entirely sure where the show is headed by having Franco play both personas, and how much drama they’ll wring from this conceit, but for the time being it’s A-OK fun, and downright hilarious when one Franco shades the other’s estranged wife.

In some ways, these two dingbats make for a curious television series setup. Eventually, Vincent will get leaned on hard by a guy named Tommy Longo, who is after some gambling debts Frankie owes the mob. Inevitably, this will be a recurring issue… as it should be. Ever since HBO ushered in the lauded modern golden age of television via The Sopranos, crime series about vile but charismatic anti-heroes have been a dime a dozen. Yet where are the series about the guys they squeeze for their bread and butter? Surely a sheep deserves a show as much as a wolf, especially as it wanders off into the woods all by its lonesome?

Vinnie appears to embody just that, as he only lightly scrapes against the main tone and tenor of The Deuce. That fleeting encounter occurred tonight when Vince leaves the safety of his flophouse closet to see a pimp who calls himself C.C. (Gary Carr) cut on a prostitute, one whom he had previously awarded the dubious honor of “bottom bitch.” Ashley (Jamie Neumann), who worries that her status as C.C.’s top earner and main squeeze is in jeopardy due to the pimp bringing on new talent, tried avoid work on the night of the show’s final scene. And she got a knife to her armpit for her troubles.

It’s a shocking moment of violence and abuse, but Vincent, ever the friendly go-along to get-along good fellow, turns his back on this act of violence. After all, C.C. also knows who Vince is: He’s the average New Yorker who simply turns away and closes the door.

It’s a revealing moment that is true to the City that Never Sleeps—then and now—and also underscores yet another ugly quality about this long lost utopia for those who dig on on an urbane ‘70s dystopia. And it likely signals that there won’t be much of a barrier at all between this world and Vincent’s as the series progresses its narrative.

For the real focus of The Deuce is on the nightlife wonder of 1971 Times Square, and the not-so-wonderful lives that populate it. Indeed, the eponymous 42nd Street is brought to life—apparently in real-life Hamilton Heights—in grimly grand fashion. When Vincent first gets off a B train for the rundown epicentre of the Theater District, he passes women servicing men by a payphone, and arthouse European cinemas bumping and grinding against nudie peep shows. John Waters and Bernardo Bertolucci alike have movies juxtaposed to this scene, and I especially appreciated a poster for Charlton Heston’s The Omega Man.

But the heart of the series will be the souls walking in front of these tokens of yesteryear. In this vein, we meet three working women who are pursuing the world’s oldest profession—and how blinding those big city lights can be.

Candy (Maggie Gyllenhaal), Darlene (Dominique Fishback), and Lori (Emily Meade) each represent the different dangers and awkward desires of this career path. Lori herself appears at first glance to be The Deuce giving itself “an out” in depicting how the sex trade uses and abuses women. Young and fresh off the literal bus of a Greyhound in Port Authority, she is picked up by C.C. who targets her as a naïve young thing in need of corruption. However, any notions C.C. has about Lori being innocent of the world are quickly dispelled when she scoffs off the free dresses he offers in the back of his Cadillac, preferring to get the free breakfast and hear his business proposition.

While it is more than likely fair that many of the women in this business enter it with eyes wide open, it could be considered a copout that the first one audiences are introduced to reveals that even if she’s new in living in this town, she isn’t exactly new to living. Fortunately, the episode closes out on the flipside, as Ashley, who also once was picked up off a bus by C.C., sees the proverbial “stick.” We also meet her at the same breakfast spot C.C. brings Lori.

While C.C. goes over with his mark the finer details of his business model, the episode lays out in the barest sense the banality of its setting. The most eye-opening scene is thus that early morning bustle in a midtown diner. Junkies and war vets, pimps and prostitutes, break bread and snort coke while going over their business strategy for the coming nightfall. One particularly short-tempered facilitator of fellatio even numbingly promises Darlene and her fellow contract players that if they do good business tonight, there will be a fancy dinner in it for them all. “Yes, daddy” is the unified response.

Darlene appears less eager to jump into the lifestyle than Lori. Having done it for some time, she still can’t stop one john from roughing her up too much in their creepy, rapey role playing game while she watches MGM’s A Tale of Two Cities from 1935. That film, like the book, is about the best and worst of times, which The Deuce appears determined to evoke while staying all in one place. But while it beams from the bright lights of New York in this era, it is weighted down by its fleshy feet of clay. Truly, the lives these women must endure is rotten.

Darlene likely gets more enjoyment watching that fairytale of beauty being discovered in the ugliness of despair than she does in her own daily life. Larry, played by the invaluable Gbenga Akinnagbe, threatens to rough her up because her first regular, weekly client did the same. And because she stays late to watch that movie, she must book it before dawn to Larry in hopes of avoiding another bruising.

She is likely not made out for this business, but really should anyone be? Lori discusses which pimp is the best for business with Candy on a street corner underneath a marquee for Mando Trasho, and both agree that these men are all pretty trash too. Lori seems unshaken getting into proverbial bed (for now) with C.C., but it’s no wonder that Candy has gone into business for herself. Unlike the other women, she walks the street without a pimp to watch over her. This gives her more money to send home to a judgmental mother, as well as her young son who stays with her. Presumably, the son is Adam (we see her saving money in an envelope for one such person), but given that her boy is with mama, it’s curious whether “Adam” is a character yet unseen.

Gyllenhaal is no stranger to complicated women and she imbues Candy with a chipper weariness to life. She is still human enough to at least try to see humanity in other people, even if they’re preppy virgins who are bargaining/beginning for a second birthday ride with their woman of the hour.

It’s a fun scene as Candy leads a boy who can only have at most 10 years on her own son up to a horrible rented room, and he whines of the unfairness of her charging him by the roll in the hay—which he blows the first expenditure of in a premature burst. When the kid mewls that she should give him a second try after he proved to be too hasty, she shuts him down by pointing out that he wouldn’t expect his father to charge more or less for a car based on the easiness of the mark. Yet Candy reveals that her cynical practicality has limits since she breaks her own rule of only paying with cash, because the wholesome kid offering the hooker a $50 cheque from his grandmother is just too sweet to pass up. So is that money.

So Candy can afford a nice view in a grubby studio apartment in Hell’s Kitchen, and Gyllenhaal can hint at a sea of calmed storms just waiting to spin again in a hazy ambivalence. I imagine that the first of these squalls will be unleashed when the pimp Rodney (Method Man) comes back into her orbit. We see Rodney offer Candy the chance to join his harem, which she wisely rebuffs. Why pay money to a guy who once in a blue moon might rough up a stingy customer when she can keep the money from all the others? But she is also whispering her ideas to newcomers like Lori, and if it starts to stick, one imagines the pimps can be as determined to squash such talk as normal industries are eager to silence any murmurings of the phrase “union.”

As for the captains of this peculiar business? We are introduced to several pimps that include C.C., Larry, Rodney, and Reggie Love. Reggie and C.C. have a particularly marvellous introduction with the former regaling the latter about why he thinks Richard Nixon is taking pimping world logic to the Vietnam War quagmire. Have Kissinger talk peace in Paris while then also starting an illegal war in Cambodia that will kill millions? It’s no different to Reginald than making his hoes think they could get cut before actually doing the deed.

This is a fascinating scene, because Reggie himself is a Vietnam vet, which may be why he’s more invested than C.C. or probably most men who came up from the working class in the five boroughs with what an American president is doing in foreign policy. However, it demonstrates the paradox of these men. Reggie, like C.C., is self-made. He wears his new money on his clothes like the spiffy hat on his head, or that fabulous cane in C.C.’s hand. Later in the episode, Rodney, Larry, and C.C. all get their shoes shined in the same worn down neighborhood that another local boy is choosing to try to police in a presumably honest way. But as persons of color in Richard Nixon’s America, the avenues of opportunity and mobility are slim, yet here they all are in flashy suits and self-deluded respectability. Their opportunism—right down to them staring at the Port Authority arrivals like predators sizing up a herd for the choicest piece to sink their teeth into—is grotesque, but it is just a reaction to the world they came up in. One where “President Reggie Love” can treat women no different than President Richard Nixon may treat sovereign nations on the side. (Fun side note: Reggie Love is also the name of a Duke Basketball player turned President Obama body man, for whatever that’s worth.)

C.C. seems much gentler than Larry, who appears like a loose cannon waiting to explode on Darlene, but for all C.C.’s smooth talking promises, he still ends up with a blade in his esteemed bottom bitch’s armpit—cut where clients can’t see the abuse.

With so much emphasis placed on a world of pimps and their prizes, and the few women who wish to be associated with neither, it makes the role of Abby (Margartia Levieva) somewhat of a curiosity. Abby is an NYU student who is an HBO dream package: smart enough to ace her exams, but adventurous enough to still shag her professor in the middle of the day.

It’s hard to gauge what role she’ll play in the series’ central plot as her main purpose in the first half of the hour is to show that vintage New York City could be a wild playground without getting involved in the sex trade. She lives with picturesque views of the Lower East Side from her apartment, and will score speed on the side for schoolmates dim enough to think Ray’s Pizza on Prince Street is somehow better than John’s Pizza. (Still, they all should check out Joe’s which will be near enough to NYU when it opens in 1975!)

Abby is an interesting inclusion because she is clearly the smartest woman on the show. Yet she likely can only become entwined in a world she views as objectifying and using women (true) if her prospects shift in a downward trajectory. That certainly almost happened when she is busted in Hell’s Kitchen while buying drugs for her classmates. And glumly she only gets off because Officer Danny Flanagan (Dan Harvey) takes a shine to the “Young Girl” in a way that would do Gary Puckett proud.

He will let Abby off with a warning if she lets him buy her a drink at the saddest excuse for a Korean restaurant on the Deuce. This brings her into the orbit of Vincent, which will likely be her doorway into the burgeoning business that he is only himself now glancing through. Mentally sparring with Abby allows Vince to prove he’s smarter than a lot in his gravity while she, in turn, provides a voice for the audience to condemn this world, even as she is undeniably attracted to its messy energy, as if it were James Franco in a 1970s midtown dive. Nevertheless, the fact that she came with Flanagan and then stayed behind with Vince might become a flashpoint later if she continues to wander up from college to explore a field trip into the more electrifying corners of the island.

Overall, The Deuce opened well. It weaves a tapestry as diverse and smeared as the population of its titular street trekking through a particularly rainy day. And it grinds to a rhythm that is far more inviting in an hour than anything seen from a whole season of Vinyl. Still, at the moment, its greatest selling point appears to be how well it has rebuilt a world lost like tears in a Disney Store. All of the personalities stood out, with Vincent, Candy, C.C., Reggie, and Abby all being particular persons of interest.

How these threads will interweave as the show’s imminent new business booms remains to be seen, yet given Simon created the series, we imagine it will come together in shocking ways. Until then, this hour is like a night out in the show’s version of the Deuce; it’s too irresistible to not spend another evening with. Maybe even another seven.