Few blockbuster composers are in as much demand as Michael Giacchino. Having risen through the ranks of video game scoring and smash-hit TV sucesses with the likes of Lost, the versatile composer has over the last decade musically defined several enormous franchises. From Rogue One to Jurassic World to acclaimed Pixar Oscar-winners like Up, there’s no end to Giacchino’s talents.

With his 50th birthday concert at the Royal Albert Hall coming up on 20th October, we were delighted to catch up with Michael to ask that all-important question: what makes a truly great film score?

Well, it’s been 15 years since I was playing Medal Of Honor: Frontline on the PS2 and now I’m sat here talking to its composer! Seriously, how hard were the tanks to defeat in that game?

[laughs] Well, I gotta be honest with you, I never played it! Only because I’m terrible at video games and they frustrate me. I loved the artwork and design and loved creating the music but I never played it. I watched other people play it though.

So what were the lessons you took from that period of scoring videogames that you then applied to writing music for films?

Well the big thing it taught me was to be organised, be concise and be fast with my writing, because the schedules weren’t long and there simply weren’t the budgets available. So it taught me a lot about the practical aspects of writing. Creatively, I spent a lot of time coming up with themes and ideas for all these different periods. I didn’t want it to be wallpaper music. I wanted it to feel like the film stuff I remembered from when I was a kid. Even though it was a videogame we could still have it feel cinematic.

So it was a real opportunity to go ahead and do whatever I wanted because, although we had Steven Spielberg producing these games and regularly checking in, we never had, like, 15 producers looking over our shoulders, the way it is on a film sometimes. It was much more of an open, creative environment, which was a lot of fun. Looking back on it, I really appreciate having that experience. So it was a nice easing in to what I’m doing now and it taught me a lot about dealing with people, with numbers and time. That was the big takeaway.

I wanted to congratulate you on what’s been an extraordinarily busy year, which has encompassed Spider-Man and War For The Planet Of The Apes in July alone. How have you found time?

Yeah, it has been hella busy these last few years. But I guess I have a very specific work schedule. I work 9 to 5. I always break for lunch, I don’t hem and haw. I don’t second-guess myself, I just sit down and write. It’s really from 9 to 5, maybe 6 if I’m on a roll. I rarely go past that because I like to have my evenings with my kids, seeing my friends, having normal experiences. Not always being stuck in a dark room.

Taking it back to the beginning then, what was the score that lit the fuse for you at a young age? What inspired you to become a composer?

Well the easy answer would be Star Wars, which was the first one that made me aware of what an orchestra was doing. But really it was the music for the films that Ray Harryhausen did. I was a sucker for those stop-motion animated sequences, monsters and all that. And of course Bernard Herrmann scored a bunch of Harryhausen movies. They were just the most incredible scores. Growing up I also loved King Kong by Max Steiner.

They were the basis but I didn’t really have an understanding this was a specific job undertaken by somebody. However they certainly influenced me in a huge, huge way. But it was when Star Wars came out that I finally made the connection: ‘oh, there are people playing this music and a trumpet sounds like that, a French horn sounds like that’ and so on. That solidified it but the inspiration came from the years prior to that. Monster movies, Sinbad movies and that stuff. I love all that.

You’re one of the greatest exponents of theme and melody we have in modern day film scoring. What attracts you to that particular mode of scoring? Do you owe that to the films you remember growing up?

Definitely. To me, you couldn’t separate those melodies from those storylines, you know? One of those themes would just put you back in the world of a particular film and I really enjoyed that. I liked the idea that I could sit there at night in my bedroom, put something on the record player and be instantly transported back to this place. Whether it be the world of Superman or Sinbad or Star Wars, whatever, it was always just a great way to put myself into a different place for a little while. It was almost like meditation, if you think about it.

So I loved that, and I loved the fact that each film had their own identity. A lot of films these days lack a specific identity. They all feel very similar in construction. There was a little bit of that going around when I grew up but for the most part… If you think about the summers where we had the likes of Poltergeist and Back To The Future for example, there were all these different films with different stories and different musical identities.

In short I don’t know how to do it any other way. I certainly wouldn’t have any fun doing it the other way. I do my best to carry that tradition forward.

At the same time many of your scores feature instrumental experimentation, from the percussion in the Apes scores to the French inflections of Ratatouille. How satisfying is it for you to dial everything back and work with those more intimate ensembles?

Oh I love doing that. I love finding a singular sound for a specific movie. And the stories I’m attracted to are the more individualised stories. That’s why I love working with Pixar. They always have something different and new. If you look at the different films I’ve done for Pixar, each one is so different from the other and it is so fun to have that opportunity. To write unique soundscapes for them. And as I mentioned, most of the time these days you don’t get that chance.

I’ll only take a project if I feel I can give it something unique. I don’t want to get involved in something that’s just background noise. That’s not to say such an approach can’t be effective as sometimes it’s a great idea. But my tendency is towards the other way. I need to make sure each project is aligned with my personality.

Well Pixar is one of your most fruitful partnerships and includes the likes of Up and Inside Out. It must be a great joy to be able to reinvent your sound with every new movie they make?

Yeah, it’s really amazing. When I look back at the films I’ve done for them, it’s always striking to me, the diversity of the projects from The Incredibles to Ratatouille, to Cars 2 to Inside Out, to Up to Coco. I’m so happy and thankful I get to do it with them. And they’re just the best because they’re after the same thing, too. Yes they do make sequels but their pride and joy are those original stories. I love tackling the standalone ones like Ratatouille or Up – the thought that OK, we’ve tackled that now, it’s out there, now let’s move onto something else. I enjoy being a part of projects like that.

Can I just say that your Married Life track from Up left me a weeping husk of a man, emotionally speaking.

[Laughs] Well they say crying is good for you.

Well I felt very good that day! We must talk about your partnership with JJ Abrams, which has encompassed everything from Alias through Lost to the likes of Mission: Impossible, Star Trek and Super 8. Was it like a Trek mind meld when you first met – did you click straight away?

Yeah, we did. The thing that’s great about JJ is that the pictures evolve and they keep getting better. There are some filmmakers who are set on an idea and that’s what they want, whereas others like to discover that idea. And I’m not happy until they’ve nailed it. And he just likes to iterate, to try new things, to continually strive to do things better. On Star Trek I remember, we worked really hard on that new theme and I wrote about, I don’t know, 17 versions of it that I wasn’t happy with. We kept on going back to the drawing board until we nailed it. It was a process to get there and neither one of us were happy with each of the initial iterations.

Neither of us have any ego about what we’re doing. There could be a scene that’s been shot and edited together and I’ll have very specific comments and then just keep going at the piece until it’s right. We’re there to support each other and help each other achieve the best possible result. That’s all we care about. It’s not about him being in charge or me being in charge. Those are the kinds of people I like to work with: very collaborative and with a desire for the creative flow to go back and forth. Working with people who just tell you what to do isn’t very fun, creatively. And there are a lot of people in this business who are like that.

You know, we need to make sure we’re still enjoying what we’re doing. Most of us are here because we’re doing what we did as kids. Many of us made movies when we were young, and we did it for fun. So to keep a bit of that feeling is important.

Lost was a notable career achievement for you. How did you keep track of all the character themes throughout the show and keep them all in play?

We kept a special log of everything and every time a new theme was introduced on the show, we’d add it to that list. When a new character turned up, when a pre-existing character evolved and so on. And the show would happen so fast. I’d have three days to write an episode and record it. It was kind of crazy.

But that was a show where they completely left me on my own and handed me episodes and basically just say, put music in it. Because they were very busy formulating the next episode. It was a great opportunity to write for me, to be what I wanted. To not feel I had to stay within the confines of a certain creative property, because it was all original. It’s a show where I like back and think, yeah, that’s all me.

You mentioned the phrase ‘creative properties’ there and I wondered what are the challenges of honouring an earlier composer’s work whilst maintaining your own musical voice? Because you’ve worked extensively in this area, including the likes of Jurassic World.

Well, I think you have to decide, what is the original part of that theme that you want to keep? Sometimes the mistake people make is overusing everything from the past and not moving enough of it forward into new areas. On Star Trek for example I knew we were going to keep [hums Alexander Courage’s TV theme] for one point somewhere but it wasn’t something I wanted to use all over the movie. For Jurassic we thought, OK at this particular moment, we’re going to hit that John Williams theme. But once we’re out of there, we’re out of there, and back into our story.

If you go too far into the past, you lose the audience a bit. You lose sight of the story you’re trying to tell. But that’s the key for all of us: telling the story that’s on the screen. Being with the characters that are in front of you, and not with the characters they’re based upon. It’s not an exact science but that’s my general rule about those things.

One of the things I love about your music is there’s a real awareness of legacy, a recent example being the use of the original TV theme in Spider-Man: Homecoming. That made me smile from ear to ear.

That was a fun thing. Kevin Feige and I were talking before 2016 Comic-Con at Marvel. And we were walking back to my car and he asked, ‘what do you think of the original Spider-Man theme?’ And I told him I loved it and would love to do a huge orchestral version of it. He then suggested that we do it and play it in Hall H at Comic-Con when we bring out Spider-Man and I was like, done!

So we did it and later in Hall H during the introduction of the theme, everyone went nuts. We then re-did it again for the movie. Again, it was purely out of fun with the idea that both excites us and that excites people like us. The people that I work with like Kevin love all this stuff.

Is it dispiriting when you compose a score like The Book Of Henry, only for the movie to be met with a degree of hostility? Because I loved the music for it yet the film ultimately wasn’t embraced by a wide audience.

You know, I try not to take it personally. Art is difficult. It’s not always going to please everyone, it’s not always going to work the way you want it to work. There have been several movies that I’ve done over the years that have got a bad shake – Speed Racer was one of them. I loved that movie and the fact it got such a bad reception was disheartening. Yet I can still watch that movie and be delighted that I got to work on it.

But that does happen and it’s not fun. It’s much better when you have something like Spider-Man or Apes and everyone’s like, ‘Yay it’s great!’ I work just as hard on those less well-received films as I do on the other ones. It’s all about the experience and even on those films that didn’t do so well, I have great memories of working on them. John Carter was another film that fell into that category, which didn’t do as well as we hoped. Luckily we’ll be playing that, Jupiter Ascending and Speed Racer all in concert at the Royal Albert Hall because it’s nice for the audience and, who knows, it maybe gives the movies a second chance away from all the bad press.

It’ll be spectacular, I’m sure. Talking about experiences, due to circumstance you were forced to write the score for Rogue One in an astonishingly short amount of time. I’ve read that film composers often produce better results when under such pressure – would you agree with that?

Yeah, I think so. When you’re boxed in you have to make things work, because you don’t have as many options. If I had had 10 weeks to do it, I might have overthought some of it. There’s something about just having to get a project done. My early days in videogames and television really taught me how to do that. Just to trust in what I was doing and keep moving forward. Without my experiences on the likes of Lost and Alias, I don’t know if I would have survived Rogue One. It would have been a very different experience for sure.

Track puns, then. Your scores are famous for them. Do you have a favourite?

Huh. [pauses] I think some of my favourites were on the Dawn Of The Planet Of The Apes album. And most of them weren’t mine, they were my music editor’s. This is something my editors and I get into when writing, preparing spotting notes and so on. It’s a tradition that goes right the way back to the beginning of Alias. Steve Davis was my music editor on that and still is today. He started doing puns. I guess he was just bored. We just took it from there and never stopped.

But there are just so many of them at this point, I don’t even know which is my favourite. From War, Planet Of The Escapes – that was pretty good. They’re either groaners or really funny, and some people in the world love them and some people despise them. They’re expecting a really serious soundtrack experience and it upsets them. They just don’t understand that I take the work seriously, but not necessarily the titles.

So it’s a competition is it, to see who can come up with the punniest title?

It’s always between me and the music editors. If there’s one out there that’s kind of lame, we always try to do better. There was a paperwork mishap on War For The Planet Of The Apes, in that the end credits was simply called End Credits. And that’s what appears on the album. Once we realised that was out there, we were so ashamed. [laughs] I feel bad about that.

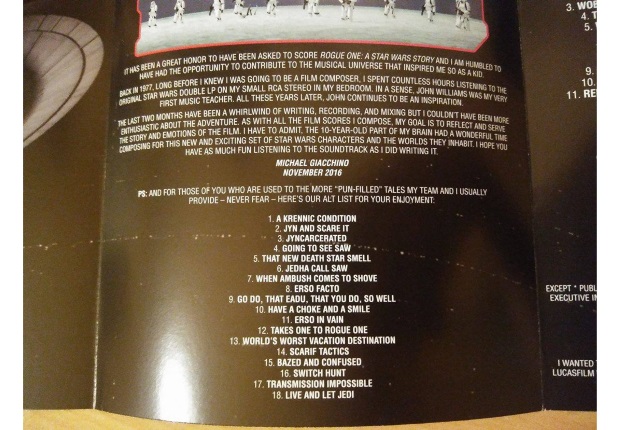

As far as the Rogue One track titles were concerned, they’re relatively sober. Was that out of deference to the franchise?

Well it made sense to do it that way because of the tradition of those scores. But we still, on the liner notes, put on our alternate track titles. So if anyone wanted to change them on iTunes, say, they could do it. It would have been weird on the actual album to have track listing like Tie-Fighter Attack followed by Takes One To Rogue One. [laughs] That would have been a little weird.

So next year is another big year – you’ve got Jurassic World 2, Coco and The Incredibles 2 all coming up. How are those coming together, because they’re all very different?

We actually start recording Coco on Monday. The Incredibles 2 we’ll probably split up, do a couple of days here, a couple of days there. Then it’s Jurassic World. Then after that hopefully a little break, for the first time in a year. I’m hoping.

Fantastic. Lastly, would you ever like to score a Jason Statham movie?

[laughs] No, I’m fine watching them! I don’t think I would help them if I scored them. I might make them worse. But boy, that guy is intense. He can do a lot of physical activity, for sure.

Definitely. Did you have a favourite of his?

Oh, what was it – a recent one…

Spy?

No, not Spy, although there was some funny stuff in that! No, it was a serious, intense, get-the-person-back type movie. I couldn’t even imagine where to start making an action movie like that. But like I said, I’m happy watching them. Scoring can go to somebody else.

Michael, it’s been a delight talking to you.

Michael Giacchino at 50 takes place at the Royal Albert Hall on October 20th. Ticket details are here.