Enter The Dragon needs no introduction. 40+ years on and its imagery is still the first thing that springs to mind when most people think ‘kung fu’. Bruce Lee’s physicality in the film is off the scale, staging and performing some of the best, most brutal and impactful onscreen fights ever. Jim Kelly oozes Blaxploitation cool. Lalo Schifrin’s orientalist funk soundtrack is the height of 70s chic. The movie looks great, sounds great and hits hard.

However, you’ll rarely hear much praise for the plot. Lee plays, uh, ‘Lee’, a shaolin monk who’s hired by a British intelligence agency to infiltrate the island stronghold of a rogue shaolin called Han, who’s into human trafficking, drug running and world domination. It’s awkwardly structured and more complicated than it needs to be but this is easy to overlook in the face of the film’s brash, colourful style. You’d think then that no one would be screaming for it to become a book, and yet…

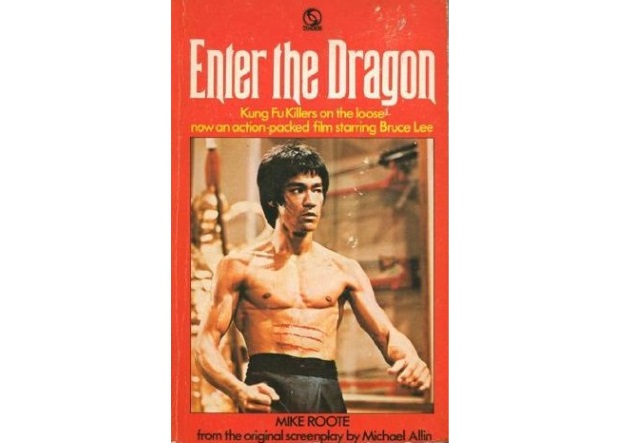

Enter The Dragon, the novel by Mike Roote, was released in conjunction with the movie and was a bestseller in 1973. Novelizations still exist today of course but back then they were seriously big business. To understand the phenomenon, remember that in the early 70s – unless a film was shown on TV or did a second round in cinemas – there wasn’t much scope for a re-watch. This was before VHS existed, so buying a book was your best way of reliving the magic.

Enter The Dragon’s novelization stays reasonably close to the film with just a few variances. Some scenes appear in a different order (the book opens with Roper and Williams fleeing the US whereas these scenes appear as much later flashbacks in the film). The intelligence agency has a name, or at least an acronym (F.A.D.E.), which is never used in the film. A few characters are described differently to how they look onscreen (Bolo is Turkish not Chinese) and some scenes are more elaborately staged in the book (there’s a long sequence inside the Shaolin Temple that, in the film, is just shot in a garden). There’s also way more sex trafficking stuff that’s pretty gross and lecherous.

The prose may be zippy but it never quite captures the energy of the film’s action. Lee choreographed the fights during the shoot so Roote, writing the novel without having seen these scenes, was unaware of which moves or weapons would be used and where. We get spirited lines like “Launching himself high in the air with a leaping kick, Lee came down like a rocket, legs and fists of steel flying” once every few pages but there’s no real kung fu described anywhere. And the legendary hall of mirrors fight? Not even in there!

However, the most interesting thing about the Enter The Dragon novel is its author. ‘Mike Roote’, it turns out, is a pseudonym of one Leonore Fleischer. I have to admit, while reading the book, I was convinced the person who’d written about undulating breasts on undulating waterbeds, and all those leering descriptions of sex slaves just had to be a man. But nope. Just a highly prolific and chameleonic novelizer.

Fleischer was largely an elusive and private figure, but wrote a huge number of novelizations under at least six names over four decades. In a 1977 edition of The Washington Post, she ‘outed’ herself and talked candidly about her career in an autobiographical feature she simply titled GASP! Two weeks later, People magazine profiled her.

If you wondered why the prose is so zippy in Enter The Dragon, it’s because it was written in a weekend on a speed binge, like all her early novels. “I would sit down on Friday night and take amphetamines,” explained Fleischer. “On Monday morning I would topple over sideways with a completed manuscript.” A few years later, she gave up the amphetamines and claimed the secret of still producing so many books was getting up early, going to bed early and not having sex. Sounds easy, right?

Her first book was an adaptation of CC And Company, a lukewarm biker film starring Ann-Margret and Joe Namath (“The bike was the central character,” quips Fleischer). Knowing nothing about motorbikes, Fleischer – who got the job on chutzpah alone – wrote it over several months of apparent agony (“It was the hardest thing I ever did in my life, next to giving up Godiva chocolates”). To hit the deadline, she had to recruit her neighbours, all of whom were frantically typing up manuscript pages as quickly as she could hand them out, but she delivered on time and the book was a hit.

Throughout the 70s, her profile grew, as did her royalty cheques. Her novelization of shaggy dog story Benji (under the name Allison Thomas) sold three million copies. Every adaptation she touched became a bestseller. Newsweek called her “the leader of the pack” and Diner’s Club magazine “the den mother of novelizers”. Her response to this was characteristically wry (“I’m a cat lover! Why am I always labelled in canine terms?”).

She spoke frankly and without pretence about the novelization process in her Washington Post feature. “I paint by numbers, I confess it. I pad out, supply background, impute motivation, invent gestures. I ride on the coat-tails of somebody else’s creation. But work is work and I’m as good as the best of the rest – just ask my agent. Ask the kids who read Benji. Ask Stephen Sondheim and Tony Perkins; I novelized The Last Of Sheila. They loved my book; I never saw their film. I never see any of the films. I’m lucky if I get to see stills. I’m writing fast on one coast while ‘they’ – the Hollywood Pantheon – are filming fast on the other.”

By the end of the 70s, she was nervous that the work would dry up. Screenwriters realised they could make more money adapting their own successful screenplays into books than they could by writing another screenplay. “Novelizers like me are in for hard times,” wrote Fleischer. “I may have to turn to another gig. Real writing maybe… I confess it scares me.”

But the axe never fell. She not only carried on novelizing well into the 90s – producing titles as diverse as Rain Man, Flatliners, Annie, Shadowlands, Staying Alive and even The Net – but also branched out into other areas, including the dreaded “real writing”. She penned her own series of high school romance novels, Hearts And Diamonds (criticized by one reviewer for its “obscure references” to ancient Greek philosophy!), some successful music biographies, a run of self-help books on ‘mental training’, and many newspaper features. Her series of Washington Post interviews with other novelists are brilliant reads, exhibiting a sharp, distinctive journalistic voice. She opens her Peter Straub piece by asking him, “How does a nice man like you wind up scaring everybody half to death? Are you just in it for the money?” and doesn’t get any softer.

Sadly, Fleischer passed away in 2009, although a lengthy obituary by her friend Carole Stuart entitled Leonore Fleischer – Queen of Kitsch gives us insight into who she was. She lived in Stuyvesant, New York and, throughout the 80s, convinced many of her friends in publishing, film production and the arts to move there too, turning it into a kind of Bohemian mecca for a certain type of New Yorker. She wrote a Sales & Bargains column for New York magazine and obsessively collected knick-knacks and antiques to the point where she wound up opening a shop so she could sell some of it on. Stuart writes, “Leonore seemingly collected everything. Teapots – indeed, she wrote a book on the subject – fish plates, Mickey, Minnie, Goofy as well as other cartoon characters, Santas, toys, cookie jars, cups and saucers, platters, board games, wooden and plastic jack-o-lanterns, and, being a writer, people.”

It’s evident in the obituary and in her writing that Fleischer was quite the character and probably a damn sight more interesting than most of her books. I think if ‘Mike Roote’ was the kind of cigar-chomping whisky-swilling pulp hack that ‘his’ writing suggests, Enter The Dragon wouldn’t be more than an mildly entertaining read. But viewing it through the lens of Leonore Fleischer’s world, it’s much more enjoyable. She was a gleefully experimental writer and her take on kung fu – while bearing little resemblance to the real thing – is actually quite hysterical in context.

My favourite example of this is maybe on the very last page. They say write what you know and I can imagine this is exactly how Fleischer felt, hitting the deadline on that book after her two-day speed binge: “Like a knight of the Middle Ages, Roper sat resting on his sword, his chin supported by the upturned hilt. His face was wet with blood and sweat but he was grinning in satisfaction. It had been a good job well done.”