I watched The Shining recently, a film I haven’t seen for at least 15 years, maybe more. The first time I watched The Shining I was far too young for what was an X certificate movie at the time – VHS had opened the door to a whole host of viewing options for young teens – and I remember being disappointed at the lack of ‘horror’ on show. But when I revisited The Shining with more mature eyes, I realised that horror wasn’t just about violence and gore, and the truly disturbing nature of the film and its underlying story became clear.

Watching it again, now, I’m surprised at how powerful it still is. Yes, Shelly Duvall’s performance is still as comically insipid as it has always been, but for the most part everything and everyone else within that terrifyingly claustrophobic environment is superbly realised.

In fact I still think that The Shining is one the finest adaptations of a Stephen King horror novel, and arguably one of Stanley Kubrick’s best works, despite the fact that fans of the book – and King himself – feel otherwise.

Now, I too love King’s books, and The Shining is a fine example of his early work, but while Kubrick certainly took liberties with the source material, I can fully appreciate why he did it. Key imagery from the film, like the dead girls appearing to Danny and the oceans of blood pouring from the lifts, simply don’t appear in the book, but they deliver incredible impact on screen.

The biggest change comes in the shape of Jack, who in the book is a man trying to find himself, trying to rescue his relationship with his wife and son that he knows is slipping away from him. Even as the malevolent force in the hotel starts to take hold of him, Jack still tries to fight it, he still wants to protect his family.

The casting of Jack Nicholson in the film instantly changed the character of Jack Torrance; it’s safe to say that Jack comes across as slightly unhinged from the outset, needing little encouragement to blame his family for his lack of success.

And the way that the Overlook Hotel takes hold of Jack is also very different – in the novel Jack’s discovery of the scrapbook is essentially the catalyst for everything that follows, and while the original movie script did make far more of the scrapbook, Kubrick decided that it wasn’t necessary. Would Jack’s more detailed investigation of the scrapbook and the information within have pacified some of the film’s critics, even King himself? Perhaps, but the fact remains that Nicholson’s Jack Torrance is a completely different animal to his literary counterpart.

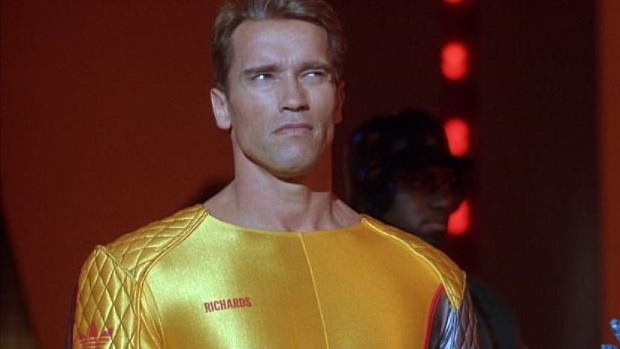

The 1987 Arnie flick The Running Man is another example of a Stephen King adaptation that was significantly changed from the source material, yet still made for an entertaining movie. In fact The Running Man was written by Richard Bachman, a nom de plume for King in an attempt to gauge the success of his writing without his name attached to it. Unfortunately, the truth about Bachman’s identity came out pretty quickly, essentially derailing the experiment.

In essence, the film and book of The Running Man have very little in common, save for the dystopian future they’re set in, and the premise of a TV show where people are hunted down and killed for entertainment. While both mediums successfully realise those two points, the protagonist, Ben Richards, is a very different character with equally different motives.

In the film the contestants on the TV show are convicted criminals competing for the chance of freedom, while Arnie has – of course – been unjustly convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. The runners are released into a designated arena, where they’re hunted by a plethora of armed stalkers, while the audience cheers and bets on who will get the next kill.

In the book Richards is desperate, he’s unemployed and can’t support his family, so he volunteers to be on the show, knowing that his family will receive $100 for every hour he survives. There’s no arena in the book, contestants are released into the world and can go anywhere, but the public can also earn rewards for informing on the runners, making nowhere safe.

While the book is a compelling read, and an arguably darker and more impactful story, the decision to change the execution so drastically for the film was probably the right one. The Running Man is a fine example of an 1980s action movie, and an ideal Arnie vehicle. And while I can’t help but wonder how different it would have been if director Andrew Davis (The Fugitive) had remained at the helm, Paul Michael Glaser still delivered something that action junkies and Arnie fans could walk away from with a feeling of satisfaction.

The key to the success of both the original Bachman book, and the eventual Arnie movie is that kernel of brilliance that King creates; the seed from which the story grows. And one can’t help but ask whether Katniss Everdeen would ever have existed if King hadn’t breathed life into Ben Richards.

But while there have clearly been King adaptations that strayed – significantly in some instances – from the source novel, while still proving to be entertaining and engaging, more often than not, it’s the directors who strive to maintain as much of King’s original vision that deliver the best results.

For me, two of the best examples of respecting King’s original vision and ultimately bringing it to life successfully come from his 1982 anthology Different Seasons. Rita Hayworth And Shawshank Redemption became Frank Darabont’s masterpiece The Shawshank Redemption, considered by many to be the greatest ever Stephen King adaptation, and for good reason.

While Drabont did make subtle changes to King’s story – most notably the personification of Red, and distilling multiple wardens into one – he maintained so much of what made the novella so compelling. Even the strapline for the movie was a play on King’s own subtitle for the book, which read “Hope springs eternal.” – no one can forget the words on The Shawshank Redemption’s movie poster “Fear can hold you prisoner. Hope can set you free.”

Perhaps it’s that understanding that King’s novella was about hope, above all else, that made Darabont’s adaptation so perfect. Yes, it’s undeniably heart breaking and painful to watch at times, but it so easily could have become a depressing, soul destroying tale, rather than the life affirming experience that it is.

Darabont’s casting of Tim Robbins and especially Morgan Freeman, given that he’s such a visual departure from the character King penned, undoubtedly help elevate the film to a level that few would have expected from a prison drama.

So enthralling and beautiful is The Shawshank Redemption that it seemed somewhat misguided for Darabont to attempt to reheat the prison drama soufflé when he tackled another King novel in the shape of The Green Mile. Yet again, though, the source material and Darabont’s expert handling resulted in another masterclass of filmmaking, keeping audiences fully engaged throughout its three hour plus running time. But as wonderful as The Green Mile is, it doesn’t quite match the sheer brilliance of Shawshank.

The second notable novella lifted from Different Seasons was The Body, which Rob Reiner adapted into his truly brilliant 1986 film Stand By Me. Here again it’s Reiner’s desire to keep as much of King’s original story intact that makes the movie as compelling as it is.

The casting, this time far more challenging given the age of the stars, is perfect; and if you were ever in doubt as to the huge loss the acting world suffered through River Phoenix’s untimely death in 1993, just watch Stand By Me.

At its heart Stand By Me is a coming of age story, but its beauty comes from the friendship shared by the four boys – their love for each other and need to support one another. Like so many King stories, what feels like the focus or plot is actually just a backdrop to the lives of the characters that inhabit the story.

While Reiner did make some changes, he succeeded in bringing the characters to life, making us feel for each of them, and ultimately understand why they relied on each other so completely. The casting of Kiefer Sutherland and John Cusack in supporting roles added further weight to proceedings, with Cusack’s flashback scenes delivering genuine, heart rending insight into Gordie’s persona.

The saddest thing about Stand By Me is the sheer volume of people I meet who’ve never watched it because they think it’s ‘a kids’ film’. I’ve convinced many that they’re wrong, and of those, the majority have been truly moved by the film when they watch it.

It’s hard not to be moved when watching Stand By Me, or when reading The Body. It’s a story that drags us back to our childhoods and rekindles the relationships we had then, relationships that meant everything to us. And perhaps that’s why one of the greatest triumphs of Reiner’s adaptation is the volume of dialogue he took directly from the book, including the closing line – “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?”

The Dark Tower, the latest Stephen King adaptation, is available now on DVD, Blu-ray, 4K Ultra HD and Digital Download. More on that release here..