At the 2004 Academy Awards, The Lord Of The Rings: The Return Of The King swept the board with 11 statuettes, equalling the records previously set by Ben-Hur and Titanic. When collecting the award for Best Picture, director Peter Jackson made a passing reference to the two films with which he had started his career in the late 1980s – Bad Taste and Meet The Feebles – commenting that they had been “wisely overlooked by the Academy at the time”.

Despite Jackson’s dismissal of his own early work, these films represent more than a curious historical footnote; they are the first steps from one of the most important blockbuster film-makers of the last two decades. When viewed from the lofty gaze of hindsight, they are not only riotously entertaining films in their own right, but a chronicle of the birth and development of Jackson’s directorial style.

Before finding mainstream success with the 1994 drama Heavenly Creatures, Jackson directed three films which can be broadly grouped as splatter-comedies, or splatstick as the sub-genre is sometimes known: Bad Taste (1987), Meet The Feebles (1989), and Braindead (1991, released in the US as Dead Alive). Although dealing with different subjects, all three films have a preoccupation with grotesque body horror, pitch-black comedy, and orgiastic displays of violence.

In retrospect, it might seem odd that the man behind these demented New Zealand oddities would go on to helm the most ambitious blockbuster movie project ever attempted. However, directorial debuts often contain ideas which young directors would revisit upon finding fame, and Peter Jackson is no exception. To this end, his early films reveal a film-maker concerned with the creation of fantastical worlds and the technical possibilities of special effects – themes which would go on to inform his pioneering efforts in big-budget cinema, from Lord Of The Rings through to King Kong and The Hobbit.

Jackson’s first film, Bad Taste, was shot on weekends over a period of four years, and launched the director’s career after being sold to distributors at the Cannes Film Festival. The plot sees a four-man team from the New Zealand Astro Investigation and Defence Service despatched to a fictional seaside town of Kaihoro, where they discover the inhabitants have fallen prey to a party of flesh-eating aliens.

This action-filled splatter fest would inaugurate Jackson’s career-long obsession with special effects, inspired by the work of Hollywood gore-maestro Tom Savini. Thus, despite the film’s miniscule budget, it makes judicious use of convincingly gruesome makeup and other practical trickery, with results which are revolting and hilarious in equal measure. One unforgettable sequence has the back of Peter Jackson’s skull flap open, requiring him to tie a belt around his head to prevent leakage of spongy brain matter.

Jackson’s expertise in homemade special effects likely explains his subsequent experimentation with computer generated imagery and digitally enhanced film-making. In many ways, the various monsters and creatures of Lord Of The Rings are the direct descendants of the gun-wielding aliens in Bad Taste. If Gollum were given a Kalashnikov, he might not look a million miles from these costumed extra-terrestrials.

Jackson’s second feature, Meet The Feebles, marked the beginning of his long-term affiliation with Weta Workshop, the Wellington-based design and effects company then known as RT Effects. This relationship was formalised in 1993 when the director co-founded Weta Digital, which has since become one of the foremost special effects studios in the industry.

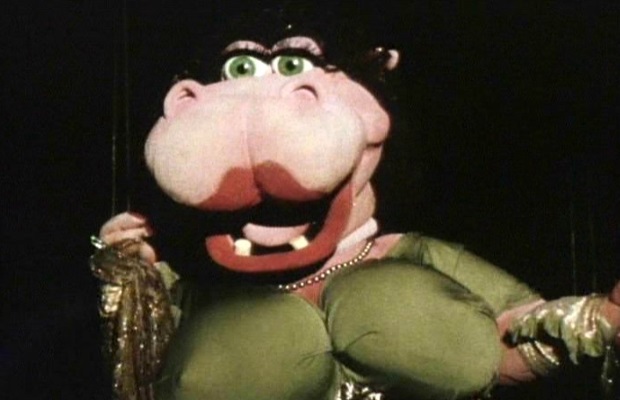

The film is broadly a parody of The Muppets, with a cast consisting of puppets, miniatures, and costumed actors. The Feebles themselves are a musical theatre troupe who inhabit a depraved and immoral world. Off the stage, they engage in various acts of excess and debauchery, including cocaine deals, murder, pornography, and coprophagia.

As gross-out comedy in the purest sense of the term, Meet The Feebles is not an easy film to recommend, and you’ll probably feel guilty for laughing quite so much. Moments of genius include a lengthy Vietnam War flashback and a show-stopping song about the joys of sodomy, while other sub plots deal with AIDS and drug addiction. It’s a far cry from the family friendly thrills of Jackson’s Middle Earth films, but traces of the director’s sardonic sense of humour may still be found as recently as the Hobbit instalments – one need only consider the testicle-chinned Goblin King from An Unexpected Journey.

The final film in this splatstick trilogy, Braindead, is the most technically accomplished, and bloodiest, of the three. It fits into what might now be called the ‘ZomCom’ genre, in the vein of Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead II or Edgar Wright’s Shaun Of The Dead. It sees a zombie virus unleashed upon 1950s Wellington, and it falls to a local mummy’s boy, Lionel (Timothy Balme), to contain the outbreak within his own home.

Braindead has a wonderful sense of time and place, with fifties suburbia providing a suitably ironic backdrop for gruesome zombie carnage. To this end, Jackson makes extensive use of genuine New Zealand locations, a practice which has been standard throughout his career. The opening scene features the Putangirua Pinnacles, a natural landmark near Wellington which was later used for the Paths of the Dead sequence in Return Of The King.

Much of the film is drenched in blood and gore, particularly during the climactic battle against a horde of the undead. This sequence, more than any other, illustrates Jackson’s talent for visceral action cinema. He shoots the convoluted set-piece with panache and clarity, deftly moving between genuine horror and hilarious sight gags, and in doing so sets a clear precedent for the large-scale battles of Lord Of The Rings.

However, the most direct descendent of Braindead is probably the grisly insect pit sequence from his 2005 remake of King Kong. The level of violence is obviously curtailed, but it takes a similarly gruesome approach to its monsters, inspiring both terror and revulsion. Peter Jackson has often stated the original 1933 King Kong to be his favourite film, perhaps providing an explanation for his continued preoccupation with violent, otherworldly creatures.

Indeed, looking back over the early work of Jackson reveals an overwhelming fascination with the macabre, a theme which has endured into later films like Heavenly Creatures, The Frighteners, and The Lovely Bones. His early splatstick movies strike a more irreverent tone than any of these films, but nonetheless deal with similarly dark overtones. In this way, the content of Jackson’s films has necessarily shifted as he has moved into more mass-market fare, but the underpinning ideas and technical ambition have remained remarkably constant.

To understand Jackson’s first few films in relation to his later work is not to diminish their own achievements, but to chart to emergence of a game-changing director. They serve as a textbook example of what film critic Mark Kermode has called the ‘trickle up’ phenomenon; that self-financing exploitation cinema has a proven track record of providing entry to the industry for genuinely talented film-makers. Above all, these films remind us that all artists must hone their craft somewhere, and that true talent transcends the limitations of time and budget.