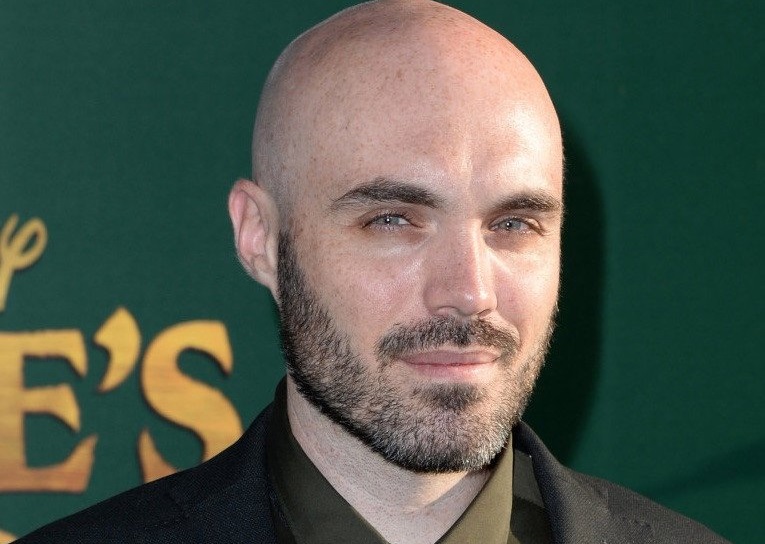

Most moviegoers know David Lowery for his very successful remake of Pete’s Dragon, but some will also know him for his indie breakout film, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. His latest project, A Ghost Story was a very personal project for Lowery who launched into it only a few days after Pete’s Dragon wrapped. Lowery has a few other projects coming along, including the highly anticipated Peter Pan remake.

Hiding an Oscar-winning actor under a white sheet for almost an hour and a half was a very bold idea. What made you decide to go ahead with that approach, and were there times during the shoot when you wondered if you made the right decision?

That idea was so central to the concept of the movie that I never wavered from it. I would never have made that movie without that bedsheet, but there were certain days on set when I wondered if it would work. I wondered if the ghost would be too goofy, or if it was too high concept of an idea. In those moments, I did not think of taking the bedsheet off of Casey and just letting him act. I just thought that maybe the movie would be a failure, because if the bedsheet was not going to work, the movie was not going to work. It was so intrinsically linked to what this movie was going to be that I never thought of [not using it]. It was all or nothing.

When did you know it was going to work? Or did you feel that way all the way through to editing?

It wasn’t until the last week of production that I finally was able to rest easy and feel confident in my choice – not only to put Casey into a bedsheet, but to make this movie in general. It took us a long time to figure out how to shoot the ghost properly. Once we figured that out, everything was smooth sailing, but there were a lot of stressful [moments]. The process of discovering how to make the ghost work was very stressful.

You took a classic Halloween costume and turned it into a tool for an actor to flex some acting muscle, but also as a canvas for viewers to project their own emotions on. We’ve seen actors being able to emote through heavy costumes in other movies, but this is very different. How much of this turned out exactly the way you wanted it to, and how much of it surprised you in the end?

It alternately is exactly what I wanted it to be. There were very little surprises in the long run. I think the one big surprise is that it was a far more emotional film than I was expecting it to be.

[Casey] gave the ghost something that was unquantifiable, but it wasn’t a traditional performance, and the emotions that came through that performance – or lack therefore – was something I had not counted on. I did not expect this movie to be as moving an experience as it turned out to be. So that was a wonderful surprise.

That’s one of the advantages of an independent movie, isn’t it? Do you think a big studio would have let you get away with that? Would a big studio have taken a chance on that?

I don’t think they would have ever taken a chance. This is something I think about a lot: Steven Spielberg was once quoted – this was back in 1999 or 2000 – as saying that if Thomas Vinterberg had come to him and pitched him the idea of The Celebration, he would have “100% financed that movie”. [Laughter].

If someone were to go to Steven Spielberg and say “I’m going to make a movie, and it’s going to be, you know, X, Y and Z, and it’s all… you know, like The Celebration, with actors you’ve never heard of, and it’s going to be shot in consumer DV, and can I have the money to do it?”, would Steven Spielberg really have given him the money to do it? I think you have to wait to see the finished film to realize that vision was there from the beginning.

I want to give Spielberg credit for saying that, but I don’t know if it would have worked out that way. By the same token, I don’t think I could have gone out and convinced anyone to pay for this movie. I don’t think I could have justified it. And I’m sure that there are folks now who will see it and say, “Sure, we would have taken that risk,” or “Yes, we would have financed that movie,” and maybe they would have. Maybe. But it would have been a much longer process, a much more challenging process, and ultimately a process I did not want to even consider embarking upon, because I knew it would just slow me down.

I interviewed Richard Bates Jr. when Suburban Gothic came out, and he said that even independent filmmaking is changing now, with financial backers demanding more and more influence on how the films are being made, almost as much as for studio films…

I certainly think that’s true. I think that everyone is very acutely aware of how risky independent movies are these days because there are so many of them being made, and the ways in which they are seen are increasing. There are more movies being made and more ways to see them, but the chances for a film to recoup its investment seem to be rapidly decreasing. So I think that investors are being much more conscientious about what they are investing in, and as a result they want to have more of a say.

I certainly haven’t experienced a negative version of that, but I can also look to my own experience making Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, and compare that to my experience making Pete’s Dragon, and when it comes to notes, and to creative limitations and frustrations on set, Pete’s Dragon was a far smoother production. It was much easier to make. It was much easier to make the movie I wanted to make, and that’s not to castigate the producers of Ain’t Them Bodies Saints in any way, but it was just that there were a lot of cooks in the kitchen for that movie, and there were a lot of different opinions that were all good and valid, but it was a much rougher production as a result.

With Pete’s Dragon, Disney was very excited about the movie I wanted to make; they were very supportive of it, and it was a smooth process. I was really surprised by that. I was expecting the opposite, but now having been through both of those, I can completely see the way in which independent films can be either equal to – in terms of the interference from the financiers or the producers – or greater than a studio film. And I want to be clear that’s not necessarily a bad thing. I think that if you have a good producer, he will be involved in a good, productive way. If your financiers care about the movie, they will be involved in a very constructive fashion, but it can get out of hand very quickly, and that is something to be aware of in any type of filmmaking.

So you went from making an indie, to a big studio film, and then back to an indie, and now you’re embarking on a new big studio film with Peter Pan. How hard is it to make the transition, or is there a transition at all?

It really comes down to the time commitment. Once you get used to making a movie for more than $50,000, the differences go away. They’re all kind of the same. They use the same equipment. The designated roles on set are all the same. The rules you have to follow are all the same. The ways in which you break the rules are usually the same. The only real difference is the amount of time it takes to make these films.

I just wrapped a movie with Robert Redford [Old Man And The Gun] that was an independent film, and we shot that in 31 days, which was a little bit more than A Ghost Story, a little bit more than Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, and less than half of Pete’s Dragon. If I go make another Disney movie, which may or may not happen, but I’m excited about the possibility of it, I can automatically just write off two years of my life, because I know that it will take at least that long to make. And that’s the biggest thing you have to understand going into these movies… that it takes a while, and you have to be willing to give it your all for that entire period of time. Once you accept that and are able to deal with that, the differences really are minimal.

Let’s talk about how you manipulate time in A Ghost Story. Sometimes, it slows down considerably, like in the pie-eating scene, and then there are huge leaps into the future. What were the challenges of making that work?

It really comes down to one’s own internal chronometer and one’s sense of rhythm, and I really just use my own taste as a barometer when it comes to those things. I wanted this film to play with time, to utilise time in a very pronounced fashion. And I wanted that to be relative. I wanted time to move very slowly in some scenes, and in other scenes for it to fly by in the blink of an eye.

Some of that is in the script. The structure is in the script. Sometimes I would include the running time of certain scenes in the script just to give the crew an idea of how long a scene might last. Other times, you discover it on set, because something you are looking at is not as interesting as you thought it might be, or sometimes it’s more interesting and you just want to make it work longer. And then, you take those shots to editing and start to slam them all together, which is how I like to describe editing; it’s a very messy process for me, and gradually it gets cleaner and cleaner as you move it along.

As you go along, you discover the rhythm, the internal rhythm that every movie has and you try to follow that rhythm. There were scenes that had very long shots that did not need to be that long. I would cut those scenes in half, or cut them out entirely. There were other times when a shot that I had filmed on set wasn’t quite long enough, and I would have to slow it down, or digitally loop it so that it would last a little bit longer. That is not done through any mathematical science or anything as exact. There is no scientific method to it. I just sort of watch the movie and feel out that rhythm and trust my own internal chronometer.

It’s interesting because it shows us how we sometimes have to endure the passage of time, while at other moments, it shows us how fast time can fly…

That’s just the way I experience time in my life. I think it’s a common phenomenon. The relative pace of time, and the way that pace changes in the course of our lives, is so profoundly noticeable. As children, we all feel like Christmas will never come, or that summer vacation is going to last forever. Time goes by so slowly when you’re a child, and then, as an adult, it goes by in the blink of an eye. I wanted this film to encompass both those types of time passage. So there are times in the movie when the seconds are just ticking by at a glacial pace, and then there are other times when life and death just go by [swiftly]. Those are both equally true to how I perceive time in my life, and the way I move through it. I wanted this movie to be reflective of both of those types of experiences.

With its aspect ratio, the movie is a square in the middle of a large rectangular screen. It’s almost as if we’re watching a home movie shot on Super 8. There are a lot of things reminiscent of home movies A Ghost Story. Was that the desired effect?

There were a number of reasons why I went with that aspect ratio. Largely, it just felt like the right aesthetic choice. It felt like it would convey the right type of feeling to the audience. And certainly, I’m a sucker for nostalgia. It’s a big part of why I made this movie in general, and I felt that the square aspect ratio with those square edges would put the audience in a nostalgic state of mind. It felt like home movies, it felt like photographs, it felt like slide projectors or View-Masters. We tried to make the images as organic and as textured and as colorful as we could to help facilitate that. We wanted it to feel rich, and old and antiquated, in all of the best ways.

It may not seem so to some viewers, but you throw in some humour in there… I burst out laughing at one point [details of exact moment redacted]

It definitely is there. The very first version of this movie I saw in my head made me laugh. It’s an inherently funny idea. It’s an inherently funny image, the image of this bedsheet ghost in an empty house all by himself. It’s also a very sad and a very lonely image. There is something bittersweet and melancholic about it as well, and I wanted to embrace all of this nuance. So I’m glad you laughed, because it was meant to be funny, almost to serve as comic relief for a brief moment before it gets sad again. The wave that the ghosts give each other… We were just cracking up on set when we shot it. It was very, very funny to us. Just as the ghost himself. It was meant to provoke a chuckle or two the first time you see him, because it’s a funny image.

It’s a strong image from our childhood. It was the very first Halloween costume I ever wore…

Exactly. It has all sorts of connotations. The key is to take that funny image, that nostalgic, humorous, childlike image and place it in a different context. And that is the route by which you get to these different emotional levels. But from the onset, it’s funny, and it’s ok to laugh. And I’m glad that people laughed.

How’s Peter Pan coming along?

I should be working on it right now. I’m in my hotel room, and I’ve got my computer, but I’m working on a different script instead. That’s just me. If there is something I should be working on, I’ll be working on something else. I’m my own worse enemy when it comes to that.

The script is under way. We’ve written about a draft-and-a-half at this point. We probably have a few more drafts to go before everyone feels it’s at a place where it can get made. It’s going well, but it’s a challenging project for me, not only that it’s a story that I’ve loved from my childhood, but that it’s one of the crown jewels of Disney’s animation empire. And there are certain expectations as to what a Disney Peter Pan movie is to be. And that’s very different from Pete’s Dragon where no one really cared – I mean, some people cared. There were definitely fans of the original, but it was definitely an under-the-radar Disney title, and we were able to make our own version without even going back to look at the original, and no one was too worried about that.

Peter Pan is a beloved property. It’s a property that was brought to the screen many, many times before, so one has to not only justify the reasons why one might make a Peter Pan movie in 2018, 2019 or whatever, but you also have to do justice to the source material. So, you can’t be a revisionist, but you also cannot be redundant, and that is a very challenging process. I think we can do it, but we are being very careful. If it has to be done, it has to be done right. Until we have that version of it, we’ll keep working on the script.

[MAJOR SPOILER FOR A GHOST STORY AHEAD – THE REST OF THIS INTERVIEW IS SPOILERY]

I usually promise no spoilers, but in this case, it’s really hard to talk about the ending without mentioning the note [left by Rooney Mara’s character in the wall of the house]. The viewers are left to wonder what was written on that note that gave closure to the ghost. What made you decide to use that approach for the ending?

I was very open to showing what the note said, if we could come up with something that would actually matter to audiences. The truth is that there is nothing that I could put there that could be more satisfying than wondering. The wondering and the questioning are intentionally frustrating, but I think audiences will enjoy that frustration more than they would enjoy seeing what that note said.

I believe that this one unknown thing is more satisfying than actually finding out. It’s a mystery that is best left unstated, and I can’t provide any solution, because I don’t know what it said. Rooney wrote down something on a piece of paper and folded it up, painted it into the wall, and that note went down with the house. So, there was something on that piece of paper that she wrote down, and because she took that movie seriously, and because she cared about the movie and the characters, I believe she wrote something meaningful, but I don’t know what it is. She won’t tell me.

You can point to the briefcase in Pulp Fiction or the whisper at the end of Lost In Translation. Those are two things I’m happier not knowing. I certainly left the theatre wondering what those mysteries were. I would rather not know. I’m happy going through my life letting that mystery hang over my head.

A Ghost Story is in UK cinemas now.